Tuesday, December 16, 2025 by Montez Press Radio #art #justice

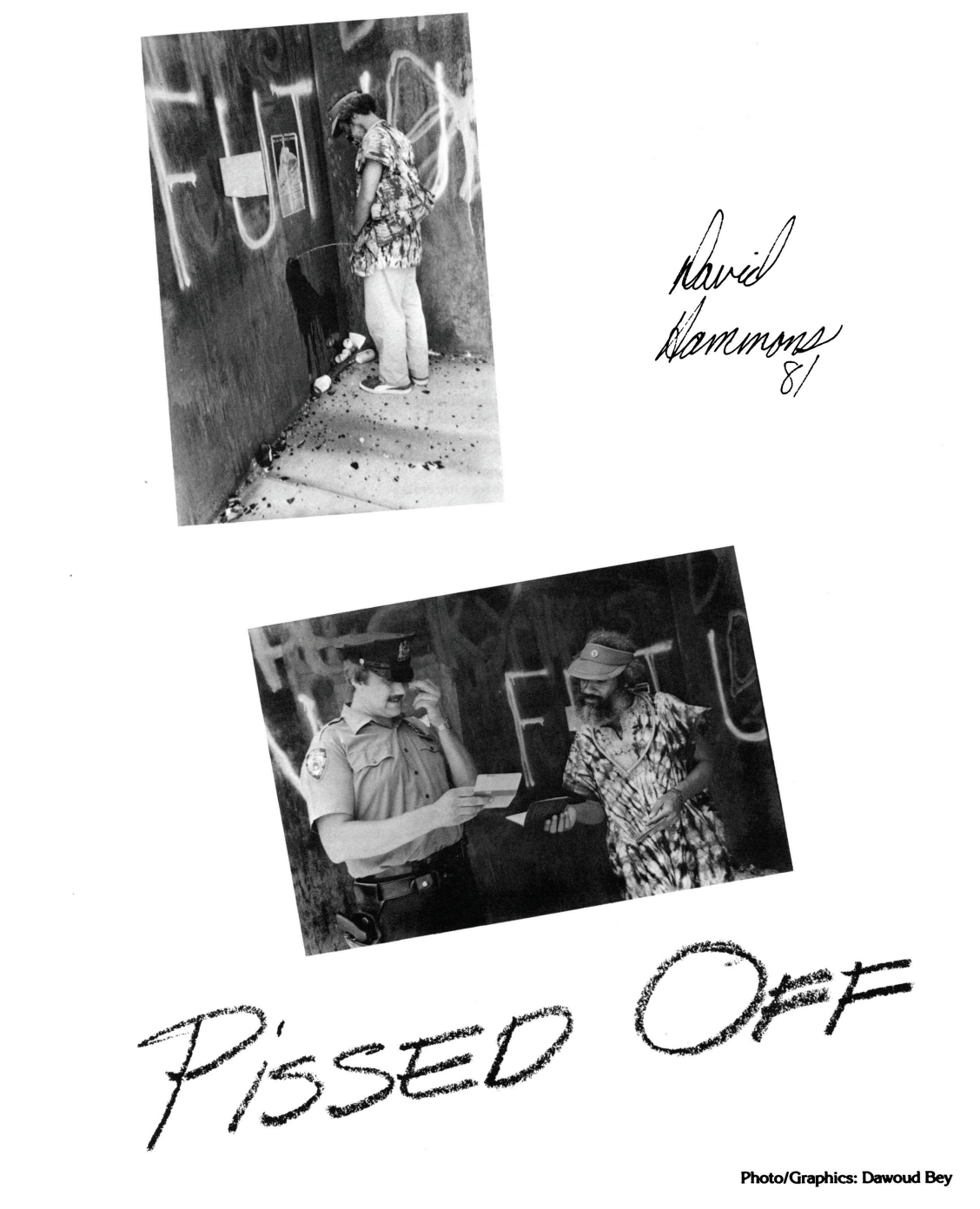

Pissed Off!

Henry Broome and Abbe Schriber discuss the ways public art participates in hostile architecture that excludes homeless people from public space.

Listen to the full segment ➚here

Bonus Links:

>>> Read Broome's full report in Art Monthly ➚here.

>>> Read Abbe Shriber's interview with 'Culture Class' author Martha Rosler ➚here.

>>> 'Pissed Off!' by David Hammons in the 1981 issue of The Flue ➚here.

>>> Listen to 'House Sitting with Mander: Architecture Against Homelessness' from the MPR archive ➚here.

Friday, December 5, 2025 by Montez Press Radio #politics #media

Anti-Advertising Advertising

From right wing teen to neoliberalism’s nemesis, artist Darren Cullen (AKA Spelling Mistakes Cost Lives) talks about the tightrope of satirizing the serious and absurd.

Listen ➚here

>>> Keep up to date on Cullen's latest public interventions via his blog ➚here.

>>> Find the full Stand Up Fall Down series ➚here.

Wednesday, November 26, 2025 by Montez Press Radio #music #performance #art

Danger Came Smiling

Linder Sterling has spent decades reshaping feminist discourse through her provocative art. In this program, she guides listeners through Danger Came Smiling, her largest retrospective to date at the Hayward Gallery in London. From her roots in the 1970s Manchester punk scene to her photomontages, performances, music and fashion, Linder’s work continues to critique gender, identity, and representation from pornography to glamour.

Listen to the full segment ➚here

Bonus Links:

>>> Watch the video tour of Danger Came Smiling ➚here.

>>> Listen to Linder's band Ludus' album The Visit/The Seduction ➚here.

Tuesday, November 25, 2025 by Montez Press Radio #music #performance #fashion

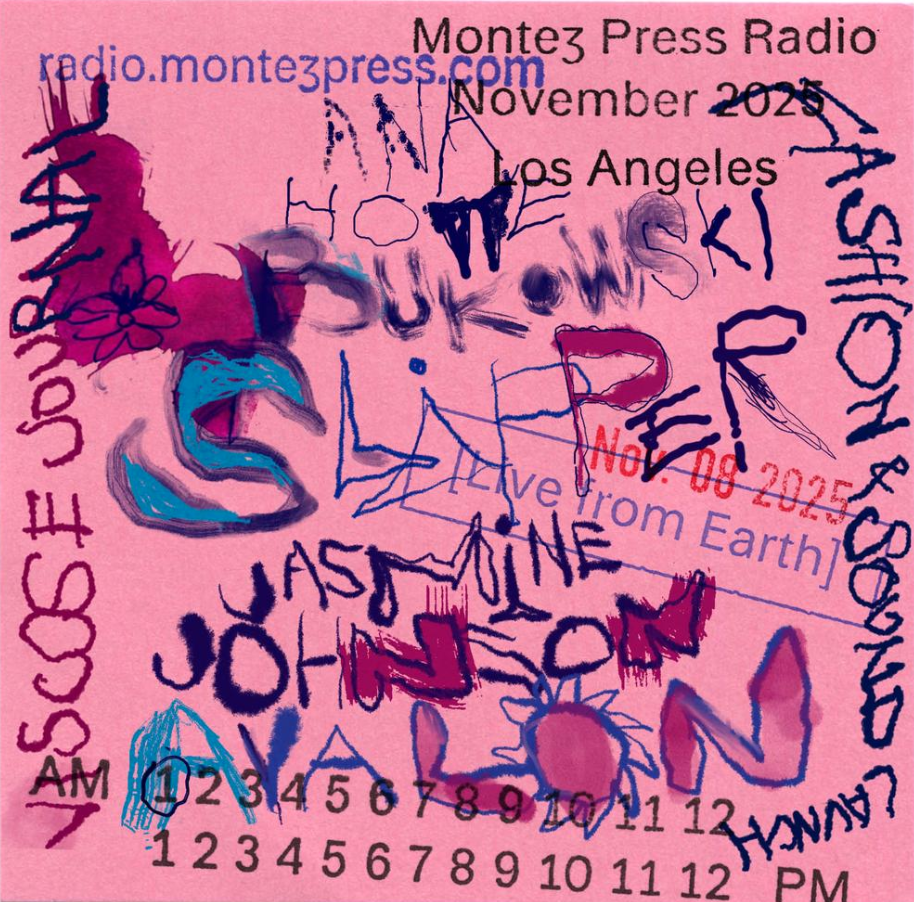

My Mantra Goes…

Chloé Maratta AKA Slipper unleashes a hypnotic stream of confessions and epiphanies, veering from the juvenile to the absurd.

Listen ➚here

Bonus Links:

>>> Buy Maratta's Diary ➚here.

>>> Find the full Fashion and Sound series ➚here.

Tuesday, November 25, 2025 by Montez Press Radio #music #fashion

Polka Dots, Pop & Parties

Ana Howe Bukowski analyzes the sensory domain of Paris’ enigmatic retailer Colette to uncover the recipe behind the perfect concept store.

Listen ➚here

Bonus Links:

>>> Watch the documentary Colette Mon Amour ➚here.

>>> Find the full Fashion and Sound series ➚here.

Tuesday, November 18, 2025 by Montez Press Radio #music #fashion

Chloé Sound Study

Tune into Chloé’s discordant Fall/Winter 2006 soundtrack with Skype Williams who decodes its chaos in his companion essay featured in Viscose Journal 08: Sound.

Listen ➚here

Bonus Links:

>>> Watch the Runway ➚here.

>>> Find the full Fashion and Sound series ➚here.

Tuesday, November 18, 2025 by Montez Press Radio #music #fashion

Leigh Bowery and Friends