Friday, March 3, 2023 by Montez Press Radio #music

Asian Dance Hybrids in the Archipelago of Kitsch

Asian Dance Hybrids in the Archipelago of Kitsch

According to Ted Gioia, old music is ➚killing new music. And honestly, when was the last time you heard anything genuinely new? Pop has largely succumbed to the algorithm, while underground music’s youth-driven cutting edge relies on supercharged kitsch, eclectic cultural references thrown into a blender, bass-boosted, and presented as a kaleidoscope of genres suffixed with “-core,” a signifier reduced to its expression of an endlessly reproducible ideal type. When it’s not rediscovering the cultural relics of the past, pop now mines the musical diversity to be found in the global margins. The most prominent currents energizing dance music today come from marginalized Black and Afro-Latin communities, from funk carioca in the favelas of Brazil to Jersey club in the housing projects of Brick City. Amapiano, Afrobeats, neoperreo; these genres have begun to capture the Western pop music imagination in recent years, genres which themselves arose out of an endless refashioning of Western musical forms in the periphery.

According to Adorno, kitsch is the “precipitate of devalued forms and empty ornaments from a formal world that has become remote from its immediate context”; for Greenberg, kitsch “has gone on a triumphal tour of the world, crowding out and defacing native cultures in one colonial country after another, so that it is now by way of becoming a universal culture, the first universal culture ever beheld.” This was back in the mid-20th century. We haven’t yet reached that universal culture, though some might argue in that direction; rather, it is now the kitsch of the global majority that is returning to a culturally beleaguered West. Perhaps this is merely another phase in the cycles of global cultural circulation, a refrain of the 1920s advent of recorded music and the scramble to inscribe the world’s sounds onto shellac.

Of course, the world is not so easily explained by the pithy universalisms of Adorno or Greenberg. This segment is instead concerned with the particular. Inspired by dance music collective Eastern Margins, this segment probes the connections we might draw between the manifestations of kitsch in different localities in Asia. These Asian forms have their own unique connotations, histories, and links to subcultural identities, often working class, marginalized, or vulgar. Like Egyptian mahraganat, Brazilian funk carioca, Balkan turbo-folk, and other mass musics, they have also often been subject to varying degrees of criminalization and censorship as well as subsumption into narratives of the nation.

In the Philippines, it’s budots—both a genre rife with potty humor and a “form of self-expression: ‘Ka-budots pud nimo uy (You’re so budots),’” according to ➚Jay Rosas. Taiwanese might call it taike, a nebulous descriptor that connotes a sort of betel nut-chewing bumpkin that has at different points in history been reclaimed for underground rock, dance clubs, and electrified ➚Taiost temple processions. In Bollywood cinema it’s the tapori who gyrates to lewd music; in Vietnam, the scourge of trẻ trâu gesticulating at loud clubs blasting vinahouse. The elite in Sinophone Southeast Asia might turn their nose at manyao and the drug-peddling gangsters they associate with the genre. And in South Korea, the spectre of ppong-tchak haunts the underground, a genre once denounced for its Japanese flavor but now speaks to an ineffable feeling of folk Koreanness; ➚according to Lee Junhee, lecturer at Sungkonghoe University, “the word ppong is often associated with subcultures, kitsch-like elements in korea, cultural elements and factors that are hardly associated with ‘luxury’ or ‘high class’ but rather, intentionally used to express vulgarity.” It’s the Korean gaksuli performer cracking sexual jokes and mooning the audience, the manyao musician hocking a loogie before the beat drops, the taike spirit of making a track whose only lyrics are “gan ni niang”—fuck your mom.

These forms have yet to be subsumed within the broader fabric of Western popular music, though the efforts of underground musicians in the diaspora have begun to lift the veil. Eastern Margins aimed to “reclaim these sounds - to showcase them in their pure emotional glory” in their compilation album Redline Legends, arguing their case as a form of experimentalism in Asian mass culture; Eternal Dragonz showcased the spirit of ppong in their mixtape ➚Cola-Tek Autobahn, mixed by Seesea and DJ Yesyes. This process of reclaiming elides a palimpsest of overlapping differences within Asian nations and regions within those nations; budots itself is a sound from the periphery of the periphery, pitted against Manila-centrism in the Philippines that has since been touted as Pinoy-field dance music. If according to Adorno, all kitsch is ideology, then what is the ideology that might be teased from this musical kitsch and its “reclaiming”?

In September last year, Boiler Room had its latest Seoul edition. One DJ stood out in particular: sporting an umbrella hat, oversized iron scissors (yeot-kawi, typically wielded as a percussive instrument by Korean candy peddlers to attract customers), and a T-shirt emblazoned with the word jeulgeobda - to be joyful. That word certainly described the crowd at the site, packed to the brim with overjoyed dancers sweating it out to ppong-tchak and K-pop. But online, the set was polarizing—a largely foreign audience clutched their pearls in horror at the kitschy, bad music that had infiltrated their precious purveyor of cool. Some native Koreans were even apologizing. While the reaction of a chin-scratching devotee to the temple of Berghain might be predictable, the embarrassment of Korean viewers is a fascinating case study of the hegemony of subcultural capital.

In the language of business techno, to describe a techno track as “hypnotic” is often meant as a compliment. But the bouncy bass of vinahouse and the incessant high-pitched squeal of budots induce a hypnotism of their own. What’s the difference, then, between the hypnotism of minimal techno and the hypnotism of these regional forms? This segment explores the dialectic between popular and avant-garde, mainstream and underground, cringe and cool, in the Asian archipelago of kitsch.

- James Gui

Listen to hours of it on MPR ➚ here

--->

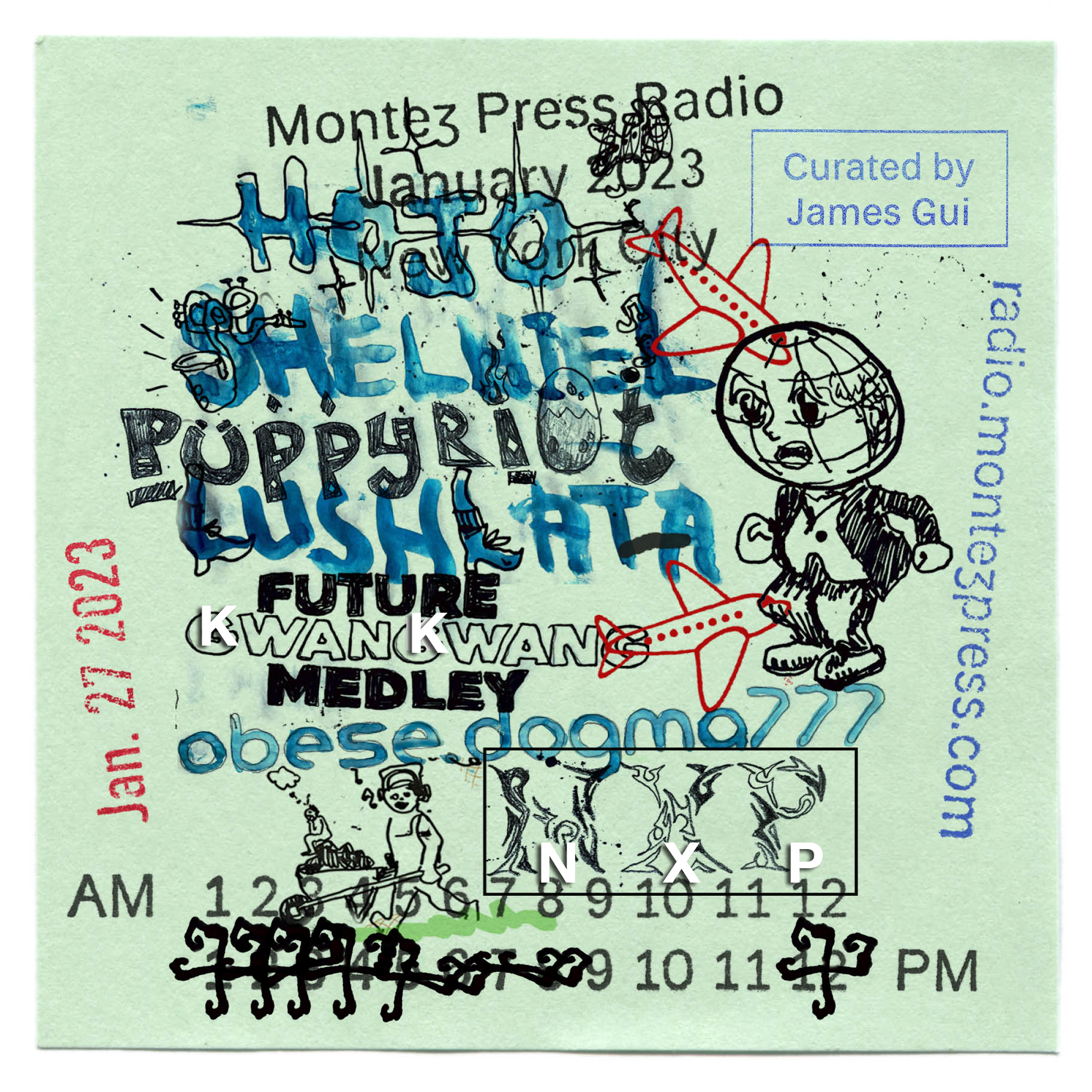

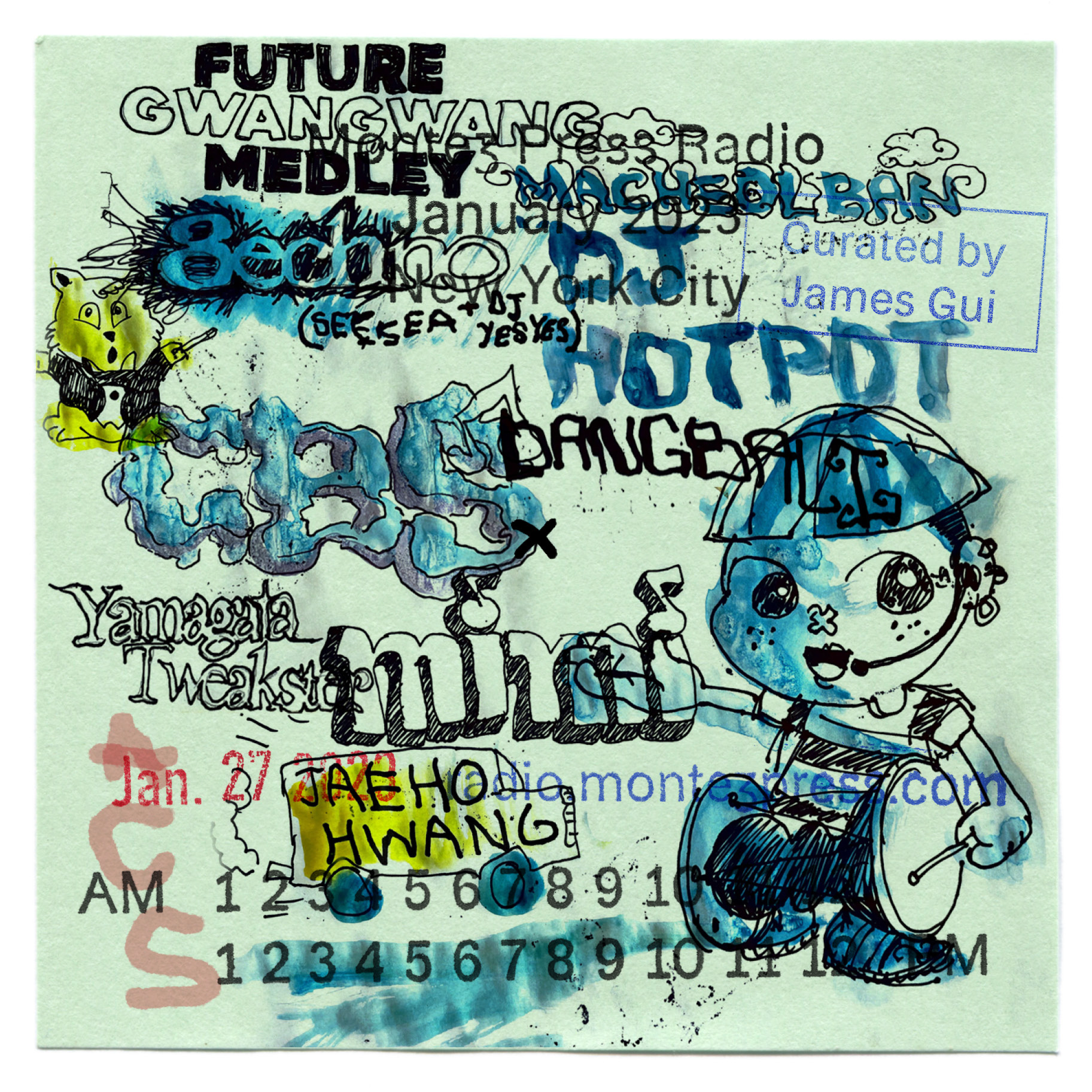

In ‘Asian Dance Hybrids in the Archipelago of Kitsch’, music writer, researcher, and DJ, James Gui ➚@zkgui , has curated 12 hours of dusty, betel-nut chewing, bass boosted, hyper-pop’d (before gen z did it) music from across working class Asia with a group of young artists working within the genres.

From ➚@therealhojo in Taiwan we hear the spirit of ‘taike’ through mandopop, a slur-cum-genre referring to pre-1949 islanders, bumpkins, and then stimulant-fueled underground music scenes.

From ➚@supershelhiel in Malaysia, Manyao is Mandopop on ecstasy- the sickly sweetness of Chinese ballads hypercharged with trance synth stabs and high-octane kicks. heard today with a global mix of Indonesian funkot, UK garage, and homegrown hyperpop.

Then ➚@_lushlata_ gives us Bollywood bass and other sounds from the margins of the Indian subcontinent with a blend of UK dubstep, jungle, drum and bass.

➚@obese.dogma777 in The Philipines we get Budots with all its high-pitched, sliding synths, vulgar vocal chops. This is one of the first electronic genres in the region that came to national prominence recently as high-profile politicians, including Rodrigo Duterte, have used it for nefarious viral political campaigns.

From ➚@_n_x_p and ➚@puppy_ri0t, we get Vinahouse the bouncy, bass-heavy club genre that is ubiquitous in Vietnam’s urban soundscape.

Then from Korea the Future Kwankwang Medley crew gives us the hyper-kpop’d Ppong chat revival, a dance music genre once associated with the elderly, typically heard at highway rest stops, flea markets, or daytime dance halls called cola-teks. Ppong and its ethos can now be heard in basement venues across Seoul. ➚@future_kwankwang_madly

If Greenberg's kitsch “has gone on a triumphal tour of the world, crowding out and defacing native cultures in one colonial country after another, so that it is now by way of becoming a universal culture”, this is the kitsch that remains at the edges, consuming, misinterpreting, and resisting a universal culture, for whom the promise of an efficient, modern and globalized future never came– kitsch’s last stand when absolutely everything is kitsch.

-Tom