Sunday, May 19, 2024 by Olivia Kan-Sperling #interviews #readings

Iconographic Literature

You can listen to an excerpt of Nicolette's new novel, Bitter Water Opera, as well as a reading of this interview, ➚here.

OLIVIA KAN-SPERLING

You just heard Nicolette Polek reading an excerpt from her new novel, Bitter Water Opera, which was released this April by Graywolf. Nicolette is a writer, but she also holds a Masters in Religion and Literature from Yale Divinity School. I don’t know much about theology or religion. In college I mostly studied quote “theory,” and especially Derrida’s critique of metaphysics, which is also a theory of writing. The main point of everything I learned in school is basically that language doesn’t work very well. For Derrida, words are always going wrong; things are always getting lost in translation; everything is very complicated, and letters are always not arriving at their destination.

This is why I love Bitter Water Opera, which begins like this: “It wasn’t impossible; it was simple. I took the letter and put it in my mailbox.” And in the very next paragraph: “The next week, she showed up.” The “she,” the recipient of the letter, is in this case a dead woman, Marta Becket. Not only has the letter done what Derrida finds so improbable, it has done the impossible: communicated—successfully, easily—with someone from another world. Nicolette’s narrator describes the sending of this letter as, quote, “something like a prayer.”

Bitter Water Opera not only tells a story but gives us a model for language that invites us to read, speak, and write differently—perhaps a little like prayer. So I asked Nicolette to write a little about the role faith plays in her fiction, especially on the level of form. What follows is our own epistolary correspondence. We’re reading this script aloud together from Nicolette’s kitchen, which I think approximates, in sound, the iconographic aesthetic we are about to discuss: formal, non-naturalistic, but still alive and filled with presence.

NICOLETTE POLEK

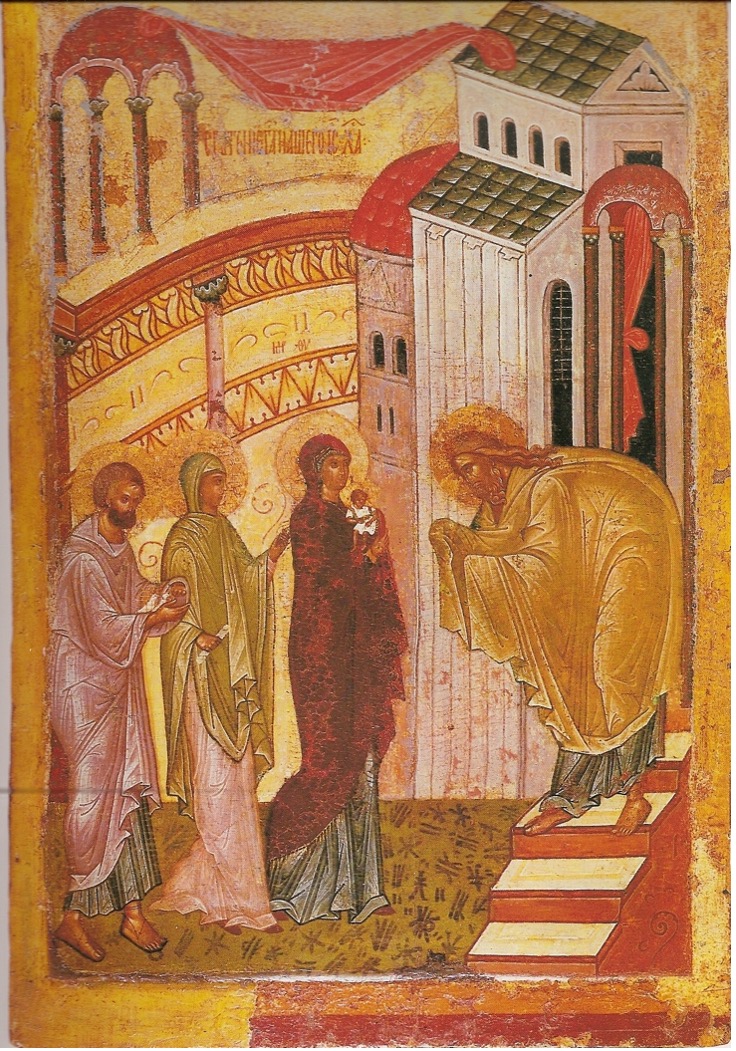

I want to come closer to creating literature that more clearly reflects a spiritual reality: one which reveals the intertwined behaviors of the soul within its materials, despite our limited individual perspective. So naturally, the icon—and especially in the Eastern Orthodox tradition— is of interest to me. Not only because the icon is something looked upon, but looked with.

When looking with an Orthodox Icon, begins Pavel Florensky’s text “Reverse Perspective,” one encounters a presence that stands outside time. This presence differs from Western icons that are “rendered correctly,” and which, as a result, feel limited to a temporal moment. In contrast, an Orthodox icon may render a figure with “obvious absurdities,” with (seemingly) wonky proportions, absence of shadows, body with both back and chest visible at once, and edges illuminated with Cinnabar pigment.

Multiple planes are visible at once. A faraway angel is brought forward, and the focus point extends outside of, and in front of, the icon, to incorporate You, the viewer, who becomes a part of the image. As opposed to there being a distinct separation between the viewer and art, the viewer is brought into the artwork, because the vanishing point is outside of the frame, where you’re standing. One world bleeds into another. The trinity swells. Giants abound. The last supper expands to seat you. This is reverse perspective.

The first time I encountered this was at an Eastern Orthodox church in New Haven, CT. Curtains moved and, panicked, I didn’t know where to put my eyes. Congregants moved around on their own accord around the church, touching surfaces; children lit candles and slipped, giddily, beneath tables. Various clergy moved through doors with angels on them, as hundreds of other invisible entrances opened within my senses. It was, oddly, like reading Virginia Woolf’s Between the Acts that winter, with its sentences that bent from one year into the next, from inside the room to a road far away, mixing the social with the natural, the sonic with the silent. Sentences that approximate a little world, both shared and set apart.

Before this, I experienced Christ in a very different context. I knew Him in a bare-walled non-denominational church, initially with much resistance, not wanting to reckon with Him. But after many years, I discovered that He had been traced boldly over my heart through the repetition of direct, simple preaching. Some call this form of worship austere, but its simplicity began to resemble a stream, or a glass world held in a raindrop. His form possessed all the features that I have—ears, eyes, mouth—which helped direct my own, as if I were a glove upon a hand. When I eventually moved, I struggled to find a church where I felt him. At one church, the preacher sighed, seemed unenthused; at another the preacher seemed confused, flitting around scripture like a that had run into a window. I sought him outside myself in all that I did, and I suppose that is how I eventually ended up accepting an invitation to attend Orthodox Liturgy, when I couldn’t find him anywhere else.

I was swallowed up by walls painted in bright pulsing pastels; corals, limes, and bright purples scattered across an otherwise dry, barren landscape. This layering of dark-to-light paint, says icon maker Fr. Stamatis, can be seen as a representation of life’s process of turning more and more towards God through the overcoming of darkness with light.—“The Orthodox icon is light-created while the Western icon is shadow-created… we start with dark colors, and then light, light, light!” he says. Light, light, light that seems like it is coming from everywhere at once, or from somewhere within the subject itself, equally distributed across the surface of a figure’s face, body, and clothes. Bright paints outline Saints and the folds of the clothes they wear.

Whether the reverse perspective is “more true” to “reality” or not, it does closely resemble our living perspective, which roves like a searchlight, multiscopic, stringing together impressions that engage with the full sensorial storehouse of memory. When I encounter a house, I see it three dimensionally, but when I remember it, or imagine it later, I may find that certain parts of it are expand and last in my mind more than others: I imagine the side yard, where two bikes lay strewn; the bay window becomes prominent and large. I imagine what it must look like inside during a dinner party. The form of the house stretches over experiences and imaginings and becomes leaky in form.

For Florensky, memory and sight work in a childlike way. But to possess the perspective of a child is a sign of genius: a child may draw a picture of a beach—crab, little waves, a candy wrapper, the giant head of a dog—that evokes the memory and lived experience of the beach, instead of the direct likeness of the beach itself. This childlike decoupage of reverse perspective is something closer to an internally true rendering of a scene, as opposed to a merely physical one. When we focus on the mere material, something more human gets lost in the process.

For many months I tried to map reverse perspective onto my writing, as a way to establish a kind of poetics of faith in fiction. I tried to apply it to narrative and poetry, thinking of Bahktin’s theory of literary polyphony, where multiple voices and perspectives expand and contract to reveal, through the tensions of their dialogues, aspects of truth.

“Interconnected phenomena form a kind of fan. The folds may develop in time, while at the same time, the fan may collapse in a way that allows the mind to grasp it,” says Osip Mandelstam.

Reverse perspective reconsiders the proportions of things, allowing for the viewer to see something familiar in a new light. The proportion play that reverse perspective employs attempts to show a “true proportion,” based on spiritual significance. Yet breaking open the familiar is not meant to have an alienating effect, as in the work of Bertold Brecht, or an absurd effect, as with many Modernist texts that are meant to show the ultimately futile nature of existence. Neither does it tip into nonsense, nor does it simply become cubism. Rather, it is meant to illuminate the “true” rather than the “real,” which, due to habit, the fog of anxiety and pain, or any other impediment, we cannot, or choose not to see with plain looking. This stylistic multi-sensorial mapping seems futile without the consideration of its original context. In the icons, one thing emerges from everything-at-once—God.

A reverse perspective in fiction would also engage with “obvious absurdities” in its arrangement, whether that would mean through fragmentation, compression, or juxtaposition, that together would ultimately work to create a clear picture. Use of sporadic CAPITALIZATION to indicate importance, or Other Experiments with Case changes, Could indicate a Kind of Extreme Emphasis found in the Cinnabar Outlines of the Icons, like in the prose of Nancy Lemann’s The Lives of the Saints.

An icon-like literature would invite the reader to recognize that they exist within the vast world that has been constructed. This new literary form, which would draw on Florensky’s insights into both the formal aspect of art and the spiritual ends it should seek, will open out from itself, instead of closing in on itself. It will reach past the cramped self-seeking of our contemporary moment, and point toward the absolute, in eternity. In our time, when now more than ever we are suspicious about the possibility of art to transcend its material conditions, a new perspective is needed, one in reverse.

OLIVIA

My favorite instance of literary reverse perspective in your book, as you have described it, comes during a sermon. There is first a sentence that comes in italics: “Words don’t fall away and disappear, but form thought shapes, lead separate lives . . . blossom, or echo, clicking into meaning years later . . .” This is the preacher speaking. Then a sentence, on a new line: “I touched my leg.” And then, again, the preacher, in italics: “Revelation finds its time . . .” Through this polyphony of voices, here you have created a fragmentation, a juxtaposition, that puts the experience of the listener (and therefore the reader) inside the words of the sermon, just as visual reverse perspective privileges the internal truth of seeing.

The three lines together also remind me of a curtain, opening and closing. There are many curtains and veils in Bitter Water Opera, as well as games of hide-and-seek. Although the first letter to Marta reaches her easily, there are other letters and emails in the book that don’t succeed: missed calls, flyers thrown immediately in the trash. Prayer doesn’t always work.

One of my favorite passages in the novel comes a little later in the scene of the sermon: “I imagined his words as small, buoyant pearls, cast from the front of the chapel and out the propped-open windows, into the town, over the house and the high wall, some falling and settling onto the ground, falling into open windows of parked cars outside the market or into the potted soil at the nursery, breathed in and carried on clothes, waiting to be encountered and revealed. I imagined all our words living out similar courses, so that we were moving through a misty network of word droplets.”

Language, in your book, seems to have a kind of material presence. It is full, rather than empty. At the same time, it can be invisible. Its meaning is not always accessible to us. Sometimes the curtains are closed. Revelation is a bit like reading a difficult text: it requires patience. When your narrator doesn’t know how to begin a prayer, she “turns to a random page” in one of her books, then “[runs] over the words like a metal detector, until something [catches her].”

How do you know when a word has caught you? How do you know when a prayer has been successful? How do you know, as a writer, when a sentence is right? What role does randomness or chance play in this? How do we ensure, as readers, that we are open to revelation in language? And what does that mean, in the context of a novel?

NICOLETTE

For one, reverence opens us up to revelation.

Each Friday from the years 2020-2022, I walked with my friend Maud Casey at the Patuxent Research Refuge in Beltsville, Maryland. We watched the park grow from season to season, meadow grasses that gradually bowed down as winter progressed. I wondered if there would be something to learn from attending the same path again and again, like robes across stone steps that impress divots over time. For months we talked about desire, God, and also about nothing, all the while poking at the remains of beaver stumps, orange jelly fungus, purple cort mushrooms, and mobs of frogs—some of which, to my horror, I ran over with my car on accident.

In Notes on the Cinematographer, Bresson states that we don’t see each other's eyes but expressions, a kind of life beneath the look, which is why we never remember eye colors. He also believes that someone who can work with the minimum can work with the most, but not vice versa. Perhaps, I hoped, I could learn to see the world through a small and special path through the woods. The more time we walked it, the more it revealed, the less I focused on myself, the more we had to show to others.

That winter I read The Art of Living by Dietrich Von Hildebrand, German phenomenologist and vocal opposition to the Nazi party. The book, about what virtues make up a good life and how they build upon each other like a staircase, points to the virtue beneath virtues, the basis behind every virtue, as reverence. Without reverence, for him, one cannot truly be faithful, responsible, or full of veracity. Without reverence there cannot be a true hope. Reverence, as defined by Hildebrand, is marked by the sort of encounter where you step back and allow the subject to reveal itself, instead of coming to it with calculation or expectation of how it relates to you. A mix of awe and humility, it allows for people and things to exist. From there, loving work can be done.

Hildebrand’s portrait of an irreverent man: “he drags himself about eternally in the circle of his narrowness, and never succeeds in emerging from himself….” Irreverence, Hildebrand says, “will be your downfall.” It is the state of the “perpetual egospasm.”

I know a sentence is right when something inside it emerges on its own and no longer feels like a sentence but a sonic, rhythmic gesture. It's as if the beginnings and ends of the words lock together to glow harmoniously. The life beneath the look.

I’m caught by a word when I can live in it. “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me” is not just spoken by Christ on the cross, but is also a direct quote of the opening line in Psalm 22 from the Hebrew Bible. What do I know so deeply in my heart that it will come forth at the very edge of death? This happens quite often in the NT, where Jesus is not only quoting the scripture, but showing the disciples what it means to embody and live its language. Jesus Himself is “the word made flesh.”

He also says “You may ask me for anything in my name, and I will do it.” I can only ask in someone’s name if I have an intimate idea of who they are and what they desire. Something I should pray more is to ask God to help me see the world as God sees it, which is a terrifying request, actually, and inevitably means to have my heart broken for so much.

There is the fruitful tension between how we expect things vs. how God works. I found a book on the 1857 prayer revival in New York City, where a group of people kept a log of every single prayer they prayed, whether it was something small like Elmar’s cold, or for the safety of their sailors during trade trips. It was someone’s job to check back into the log and detail the outcome… to track how, in some way, each prayer was answered, often in different ways than they asked for, and often on different timelines than they wished.

There is a mystery in all of this though. Does God—who is eternal, unchanging—“respond” to prayers? Or, is Kierkegaard right that prayer doesn’t change God—but the one who prays? This all gets very difficult, on the edge of what language is capable of articulating. One way of discerning the effectiveness of prayer is in the fruits: Prayer has helped me grow in humility, patience, repentance, serenity; certain bad habits have fallen away; and so on.

OLIVIA

Another one of my favorite moments in the book is in the car, when our narrator is speaking her thoughts, as they come to her, into the voice recorder app on her phone. This is something her mother used to do. Do you do this, too? When, and why? What does it mean to speak when there is no one there to hear you?

NICOLETTE

Last autumn, when I taught at Bennington college, I had a three hour commute both ways. At first I busied myself with podcasts and music during the drives, but soon enough began talking to myself. Sometimes I practiced externalizing thoughts or worked out ideas I would explore in class. It was my way of engaging with language as an outfit. I was never very comfortable speaking—I was an only child, my parents were in the process of learning English. One of the most difficult hurdles for my father was the “th” sound, which he would practice again and again around the house. My mother had a plastic bag with words and their definitions written on thin strips of paper that she pulled out while waiting in lobbies. I had a small handheld tape recorder where I practiced my “public voice.” Speaking, when there is no one to hear me, feels a little bit like handwriting on paper with no lines. It becomes a kind of reverse perspective. I am the recipient of what is spoken, which both swallows and stands outside of me. The rehearsed language overwrites the interior language and is easier to access when I am later required to speak to someone else.

The Eastern Orthodox church has a strong emphasis on embodied worship. There is quite a bit of external movement—crossing oneself, prostrations, etc. As I mentioned earlier, there are many ways to enter. This is the hardest part for me. As a Protestant, the most I’ve done, physically, is lift my hand up during a hymn, stand and sit at various intervals, or touch the shoulder of someone I prayed for. But the physical brings me there too. I sing the beatitudes during liturgy and then find myself singing them throughout the day.

There’s Stanislavski’s method of acting, which involves disturbing and reconstructing the internal, and Michael Chekhov’s technique, which creates an interior through a physical action. I know nothing about acting, but I liked Chekhov’s idea of the “psychological gesture” which is a physical expression that one performs to reel themselves back into their character—I tried having one for Bitter Water Opera, and in the first section, before I wrote, I enacted Gia reaching to step onto a ladder, but this practice eventually fell away. What stuck was praying before writing.

OLIVIA

I also wanted to ask you about stage sets and theater. In the excerpt of Bitter Water Opera we just heard, the narrator has gone to visit a defunct opera house in the desert. For Florensky, linear perspective—the supposedly more “realistic” form of perspective revived in the Renaissance by painters like Giotto—can be traced back to the techniques of trompe l’oeil used in theater sets. For him, these illusions are the enemies of truthful representation. Our narrator’s greatest moment of revelation comes in the desert, when she is (quote) “surrounded by emptiness” and “doesn’t wish to fill it.” Why did you choose a dead ballerina, and a desolate opera house, as the focal points for this novel? What role do the props, cardboard cutouts, and other representations our narrator encounters (or imagines) play in her faith?

NICOLETTE

The narrator loves false fronts, fake towns, and stage sets. Here is something a friend told me, over pastries, while I was writing the novel:

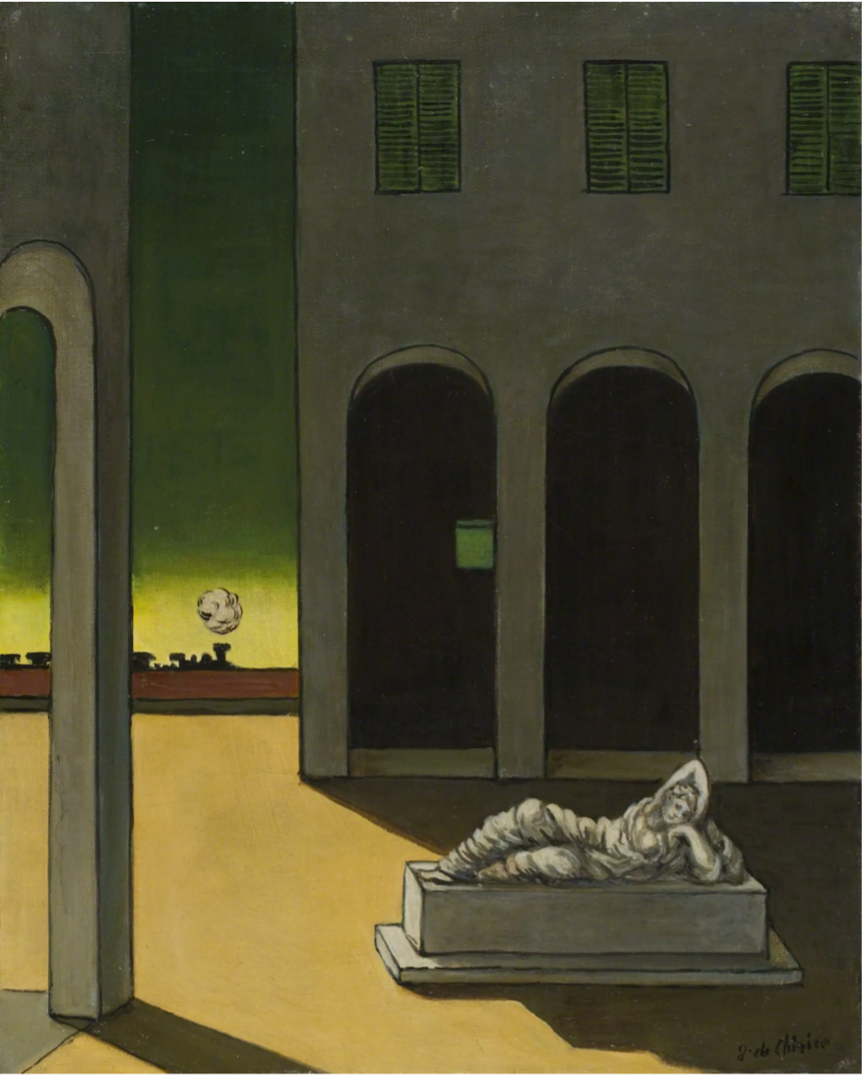

In 1911, the painter de Chirico no longer wanted to be a surrealist. He created an entire metaphysical movement in Italy but came to despise it six months later. No more paintings of towering columns, dream-like facades and eerie emptiness; he desired realism instead. Plush landscapes. Grapes in a bowl. Horses on the beach. The Old Masters. People hated it. They wanted to go back to his images of disembodied hands and the sun tied down with string.

De Chirico renounced all contemporary art but still needed the money, so he made fakes of his earlier work. He skillfully backdated them, and was able to live off the person he was in the past, gradually releasing these “originals'' that he had supposedly “found underneath his bed.” He was simultaneously able to profit off his successful movement while denouncing it. Collectors joked that his bed must have been six feet tall.

This controversy is what invented the term verifalsi, or “true fakes.” In my narrator’s weakest moments, she wishes to be deceived. She wants a kind of Potemkin village, or a place given a grand exterior facade to obscure their shabbier reality. The controlled comfort of artifice allows her to both distance herself from life while looking at it slant.

The first Potemkin Village, however, was storied to be for love, when General Grigory Potempkin wanted to impress Catherine the Great of his town’s ordinariness by creating an elaborate facade that could be seen from a carriage ride. But Potemkin Villages as we mostly know them are insidious and indicative of an authoritarian regime, manipulative and dishonest, akin to prison, or places where inhabitants are immersed into the depths of dysfunction, while onlookers believe them to live in paradise.

A lie always creates fine rips into reality, in ways one cannot actually predict and perceive. Satan doesn’t have his own raw materials. All he can do is distort and twist what already exists. In the case of my narrator, Gia’s comfort in the stage set of her life is the auspicious permission for inaction.

There’s a category of “fake town” that has a positive utility, for example, there’s an entire village in the Netherlands created for dementia patients, so that they can wander around without harm. The grocery store employees are in fact hospital employees, and the streets are empty of cars or people outside the community. There are theaters and bingo halls, fake currency and fake jobs that patients can secure. If anyone forgets their boundaries, the workers in the town step out to bring them back to the safety of reality, which, in this situation, is a combination of high budget staging, and touches of carefree nostalgia decor (juke box, soda fountain, or, depending on the country, Communist-era housing).

The dementia village’s conception of “truth” is murky, its facade is not exactly geared towards deception, but remedy. The inhabitants too have a morphed experience of what “truth” means. The false front of the dementia village is an attempt to capture the truth of the false front of dementia, where what is seen no longer corresponds with lies beneath. Regardless of its remedial quality, this breakdown of reality is a sign of decay.

I’ll end with this. I can reasonably hope and believe in a God behind the created world, in which all life itself retains and expresses a kind of thumbprint or DNA of its source. Because of this, I believe that the God who puts life into motion is also alive, and that the created world recognizes God—even if it doesn’t possess the language or awareness for it. Globally, we have lots of language for spiritual experience, or transcendence, which I think this points to.

Gia, in Bitter Water Opera, comes to God apophatically, or by seeing what God is not. First she obsesses over Marta Becket, then looks to nature, and then art itself. If she is constantly distracted and listening primarily to the created world, like nature, or herself… or if she’s distracted by the creations of the created world, like power, money, art, she finds herself drifting into derivatives or shadows that keep her at a pale stage of existence that doesn’t hold up under the pressures of existential despair. Moving her heart away from the created world and opening it up towards a creator, either through prayer, or silence, allows for her to recognize and feel God’s presence, and appreciate and witness the created world in a much richer way.

This, finally, brings her to the gospels. God, ultimately, cannot be totally discerned or comprehended, yet in Jesus, the incomprehensibility of God is comprehended through a particular individual at a particular time, and in individual relationships. Universals are always understood through particulars: We understand love through our love for a particular person; we understand courage through instances of courageous action, etc.

In BWO, I wanted to map out a specific consciousness that begins to stretch towards God, because I wondered if it could allow someone to imagine what it would look like for themselves. Like reverse perspective, I wondered if it would be possible for someone to be included in that language, to try it on, and then later access it in their own way and look at the world with it.

anon

Thank you both for this very insightful and inspiring conversation!

anon

Thank you both for this very insightful and inspiring conversation!