Monday, April 5, 2021 by Montez Press Radio #interviews #justice

Let the Record Show: Sarah Schulman

Back in September 2019, we had the honor of speaking with novelist, playwright, nonfiction writer, screenwriter and AIDS historian Sarah Schulman, focusing primarily on ideas from her books Conflict Is Not Abuse and Gentrification of the Mind. The transcript from our conversation is below, or you can ➚listen to it in the archive. At the time, she was working on an 800-page history of active New York. Twenty years in the making, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993 is finally about to be released and can be found ➚here. Thank you Sarah!

Interview with Sarah Schulman

Transcription by Carly Sorenson

Thomas Laprade: This is Montez Press Radio, it’s two o’clock, Saturday afternoon. We have Stacy Skolnik and Sarah Schulman in studio. It’s a pleasure to have you, Sarah. If you don’t know, Sarah is a novelist, playwright, nonfiction writer, screenwriter, and AIDS historian. Stacy Skolnik will be talking to her, I’ll be sitting here, I might chime in here and there, might ask stupid questions.

Stacy Skolnik: Thank you for joining us, Sarah. I feel like it’s really cool to have you here because not only do I respect all the work that you’ve done and appreciate the many hats that you wear, but you have been mentioned perhaps more times across segements than any other. We’ve been on the radio for about a year, and in various segments and various topics in various countries, your work seems to arise.

TL: It came up in London a lot.

Stacy: So it’s really cool to be able to put your work and yourself in conversation with other stuff that we’ve had on air. I first was introduced to you through the Lesbian All-Stars series that was happening through Belladonna*. You organized--

Sarah Schulman: A tribute to Belladonna*, yeah.

Stacy: Yes. That was a great reading. James Loop, who’s been on the radio a bunch, said, “You should totally get Sarah Schulman on the radio.” I approached you, and you were so open to doing it, which is -- Tom and I talk all the time about how we really appreciate the people who say, “Yes.” [laughs] It’s cool to have you here and thank you for joining us. The first book that I read of yours was Conflict is not Abuse, and I am really intrigued by the ideas that are shared in this work. I thought that maybe we could start today with -- I mean, feel free to decline -- talking a little bit about Conflict is not Abuse. I’m curious if there’s been any pushback to the ideas that you’ve shared in here. Would you like to maybe tell us a little bit about, sort of an annotated version or the main idea of what Conflict is not Abuse is trying to get at?

Sarah: There’s two main constructs in the book. The first is something that we are all witnessing right now when we have Trump say, “It’s a witch hunt!” and it’s so sad and he’s a victim, when actually he’s a perpetrator. He hides behind that. Yet at the same time, he puts blame on immigrants for pain that is caused by the 1%. It’s a deflecting system. So that’s one of the constructions that I look at. The other is the similarities between supremacy and traumatized behavior, and how when people are raised in supremacy they really hate difference. They feel that they have a right to never have to confront difference, so if they’re asked to question themselves in some way, they see that as an abuse or an attack. But when we’re traumatized, sometimes it’s so hard for us to just keep it together that when we’re asked to be self-critical, that can be so overwhelming. That simple difference can appear to be a kind of attack when it’s not. So the similarities there are the other dynamic that I’m dealing with in that book.

Stacy: Did you find that, after this book was released, did people conflate your critique with a type of victim blaming, or…?

Sarah: The biggest attack on the book was before it was published.

Stacy: Typical. [laughs]

Sarah: Someone who had never read it (because it was still at the printer) wrote that I was telling people to call the police. Which of course is the opposite of what the book is saying. And this thing was shared like thousands of times and circulated for years and it’s made a lot of people have the worst assumptions about me. I’ve tried to address it, like I’ve said to people, “This is not accurate. Would you like me to send you a free copy of the book?” And they’re like, “I don’t want to give you my address.” All that. There was one person who wrote a very negative piece but she mischaracterized the ideas. Those were the two biggest takedowns. Now of course, it’s a book that’s impossible to agree with everything. There’s too many ideas in it. So most reviews are interactive, like there’s some things that they’re intrigued by, there’s things that they like, there’s things that they reject, there’s things that they grapple with. And that’s great. You know, the ideal is for the person to accurately state my idea and then give their response.

Stacy: Yeah, this idea of interaction is something that I’d like to come back to later, maybe as we move more into a discussion about Gentrification of the Mind and ideas about community. Something that I’m curious about is, I feel like there’s a very simple idea at the heart of Conflict is not Abuse, which is, talk. Talk it out. Be patient with each other, rather than jump to conclusions or make assumptions. Discourse is necessary in order to progress.

Sarah: On the large scale as well as the small scale.

Stacy: I’m wondering, though, if there are criticisms that are unjustified, that maybe don’t warrant a response. It seems like your general approach, though, is like everything, almost, deserves a response.

Sarah: I wouldn’t go that far. You know, I couldn’t get the book published in the United States. I mean, nobody would publish it and I mean nobody. I went very low, and I couldn’t.

Stacy: Wow.

Sarah: And the main reason was because I use HIV criminalization and the murder of Gaza in 2014 as examples of larger paradigms. In America there’s so much anxiety around both of those questions that they are only treated discreetly, and to put them as an example of a human dynamic, I think, was just too much. So ultimately it was published by a small, queer press in Vancouver, Canada, Arsenal Pulp Press, and I thought, Okay, no one’s ever gonna read this book. It wasn’t even reviewed in Publishers Weekly, which has reviewed almost all of my 19 books. So I thought, Okay, this book is dead. And then people started just posting about it. I mean, it just started to appear, and then it became this enormous conversation. To date we sold almost 30,000 copies. Eventually Publishers Weekly did review it five months later because they had to, because so many people were talking about it. So really, it was this book that was propelled by readers.

Stacy: It feels so timely to me, in the sense of this cancel culture that we live in. I was curious if you feel that there are any parallels that can be drawn between a culture of scapegoating, which is what you’re talking about in the book, and cancel culture.

Sarah: I think I mentioned it once in one sentence in the whole book. I wasn’t really thinking about it because it’s just generational. But then when I started to tour with the book, suddenly I was having 200, 300 people in the room, in like Seattle or San Francisco or Montreal, and it was all young people. It was people in their twenties, and that’s what they wanted to talk about. So it translated.

Stacy: There’s one excerpt in that book that I -- actually, can I read it?

Sarah: Sure.

Stacy: Would you like to read it?

Sarah: I don’t have my glasses.

Stacy: Let’s see if I can find it really quickly. [pause] So this is at a moment you’re talking about -- maybe there’s a connection between cancel culture, #MeToo culture, all of these cultural phenomenons...

Sarah: Although it’s before #MeToo.

Stacy: Yes. But I read this probably a month and a half ago and it feels very of-the-moment. But you write:

While some sex crimes are crystal clear, others are entirely about perception. For some women I know, having sex with their partner at times when they feel ambivalent or not fully engaged, is defined in their minds as coercion or even abuse. They find it objectionable or even damaging. For others, that is part of the literal making of love - the idea that we give to our partners in moments when we are not 100% engaged, just as we negotiate in other ways in relationships. Or in terms of casual encounters, quasi-unpleasant to negative sexual experiences are devastating to some, and just the way things go to others. How previous experiences of trauma contribute to an individual’s understanding of whether or not an experience is abuse is a factor that we do not have a process of integrating into our understanding of objective crime or objective justice. How about how some experiences permanently mark some people while not affecting others makes objective standards of right and wrong difficult to establish?

Sarah: Exactly.

Stacy: I feel like that is so important.

Sarah: That’s why you have to talk to people, because if you just have a rule, You can’t do this, it doesn’t make any sense. You have to individuate every situation and find out, how does the person feel? Why are they suffering? What is their history? What do they need? Instead of having rules. Do you know the writer Olivia Lang? She’s a British writer and we were talking about this thing in California about how if someone’s drunk, they can’t consent. And she said, Well then, no English person could ever have sex. [laughs]

TL: That sort of reminds me of this other phenomenon that maybe runs alongside the cancel culture thing. There’s this phenomenon where it’s like, people aren’t allowed to speak on things that, that their own suffering, that their own experiences don’t have anything to do with. There’s this phenomenological --

Stacy: Like who owns certain experiences?

TL: Yeah, who owns a certain suffering. Are you allowed to participate in the conversation about that suffering? For example, we had this poet and artist on here, Vanessa Place, who makes work about rape jokes. If you didn’t know this and you heard one of her pieces, you’d probably sit there and -- if you didn’t know who she is and what she does -- she’s a criminal defender -- you’d probably sit there an wonder, Is she a rape victim? And then you’d wonder, Is she allowed to do this if she isn’t a rape victim? People have a lot of trouble with that work and I think there’s something about… I don’t know, what do you think about this?

Sarah: I think right now, we’ve linked being heard to somebody else being punished. In every situation, people only feel heard if the person they feel hurt by is punished. So we’re always running around trying to figure out who’s right and who’s wrong, so we know who to punish. Now, part of the problem is that punishment doesn’t work. I don’t have any examples of punishment working. So if we could separate taking people’s suffering at face value with them not having to justify it, and forget about punishing people right now, then everyone would be eligible for compassion and nobody would have to prove or earn the right to be heard, which is the situation that we’re in now.

TL: Yeah, I think that’s such a good way to put it because then what you have is people competing about their suffering. Like, I have more of a right to talk about this thing, or I have more of a right to this platform because my suffering is greater, and that just turns into this weird competition of the Suffering Olympics. It happens a lot in the arts, where your suffering is content, you know? In my little art world it’s just like --

Sarah: It works for some people, because people care that those people suffer. For other people it doesn’t work at all because nobody cares what happens to them. It’s very hierarchical.

Stacy: You’re sort of suggesting that if we can generate more discourse, we can -- I feel like ‘truth’ is a word that comes up a lot in Conflict is not Abuse. I guess I’m just wondering when the truth, and perhaps even abuse, is subjective. How can we discern -- actually just the fact that you said “punishment doesn’t work” puts my mind in a tangle, because I’m like, Well then, what is the objective?

Sarah: The objective is to…when people are in pain, we take them seriously and address their pain.

Stacy: But what do we do about the people who caused pain?

Sarah: Well, it depends. It depends on who they are, and it depends on the situation. In the book I give a lot of very specific examples of things, because I feel like in any situation, the specifics are very important. One of the people I learned from, Catherine Hodes, who taught me about this conflict and abuse dichotomy, she’s a social worker and when she talks to clients, she asks them for the order of events. You know, to really get precise so that we can all understand what’s going on. Take an example like Columbia University and the question of a male student being an offender. Obviously, there’s a lot of male offenders. It’s overwhelming how many there are and they’re in every milieu and we have no way of dealing with them. We have to come up with a way to deal with male offenders. But if you take a private university like Columbia and you have a male student who, a woman feels that he’s an offender, and your solution is to expel him, all you are doing is kicking him out of the gated community country club and putting him out into the world of women who don’t go to Ivy League schools. So it’s like you expel him from a certain class but you haven’t addressed any of the issues. I talked to somebody who did a study about sexual abuse complaints at Columbia and she said that there’s a small group of people who really are predators. They really enjoy breaking other people’s will. For almost everyone else, it’s a gray zone. People, especially young people, are very confused about sexuality, they have all their messages from entertainment, they don’t know how you get from here to there. But also, two people can have the exact same experience and one person can be devastated for life, and the other person can be like, “Oh well,” and it’s because of who they were before. It’s our histories that create how we perceive the present. That’s why we have to individuate. That’s why it drives me crazy when people ask me to hurt other people. It happens all the time. They’re like, “You shouldn’t talk to her. Why did you invite him? Why are you working with her?” If someone’s telling you to hurt someone, the very first thing you should do is call up the hated object and ask, “Why do you think this is happening?”, instead of shunning them. I’m 61 years old and shunning goes on FOREVER. It never ends. There are people who have been shunning me for 40 years.

Stacy: We’re trying to foster, here at Montez Press Radio, a safe space, an inclusive space, a space where everyone who walks in the door can feel comfortable no matter what type of art they make, no matter what their identity is, all types of ages, races, you know, whatever. And if someone comes into the space and violates the trust that we’re trying to build here by using a bad word against someone, threatening someone, is there another alternative to telling someone, “You are not welcome back here”? Is that shunning, or…?

TL: [laughs] You’re literally talking about something that happened yesterday.

Sarah: Like I said before, it depends specifically on what occurred, how the people it happened to, feel about what happened, and then what has been the process of that person. Like, if somebody says a word you don’t like and you kick them out forever, no. Or somebody might do something outrageous, but the other person just thought that they were childish and doesn’t really care that much. Or maybe, if you talk to them, you can get somewhere with them. Or maybe you can’t. You know, it really depends on the individual.

Stacy: So in that way, you feel, perhaps, that we do have responsibilities to people who abuse or cause pain? We also have responsibilities to those people in addition to those whom they’ve inflicted pain upon?

Sarah: Exactly, because it’s so many people.

Stacy: [laughs] I think we all cause pain.

Sarah: That’s right, everyone causes pain. So if you’re overstating harm, you could turn everyone into this horrible monstrous abuser and then you’ve shunned everybody.

Stacy: [laughs] It’s true. ‘Peace’ is also a term that’s used a lot in this book, and I’m wondering -- at some point I was like, What is peace? What would you, in your opinion, I mean, is there a global definition or is that also specific to --

Sarah: No, I think everything is specific, you know? People need to communicate about what the situation is. If you’re talking about Israel-Palestine, in my view, if people are living in the same area, they should be able to have absolutely equal rights and equal say in what happens there. Until that happens, there won’t be any kind of justice, so the violence can’t be resolved. My book is very much about Palestinian rights.

Stacy: Something I noticed that was very surprising to me, but I guess also not that surprising, in my research about you, I noticed that there’s a site called Rate My Racist Professor, and you are on that site because of your politics surrounding Israel-Palestine, and I wonder if you feel that in that instance, that’s an overstatement. Where on the spectrum of overstating harm, like, who in that scenario is -- that’s a person who feels like they are being harmed, suggesting that you are racist against them for being Jewish, even though you yourself --

Sarah: I was accused of anti-Semitism by the CUNY Task Force on Anti-Semitism at where I teach, at the City College University of New York. There is no CUNY Taskforce on Islamophobia, or on Racism, only anti-semitism. I had to go before a panel. The person that was put in charge of it was the lawyer who had defended Dominique Strauss-Kahn when he raped the African woman in that motel. Anyway, I had to get a lawyer from Jewish Voice for Peace. You know, it was insane. I had to wait six months to get a report out on me, and then I was exonerated. It was completely absurd. It’s Kafka-esque. I’m on every website, and I’m proud of it. It’s a badge of honor because I made my stand with Palestinians and that’s the way it is. A lot of other Jewish people do too. I’m on the advisory board for Jewish Voice for Peace. We have 18,000 members. You know, it’s the largest Jewish pro-Palestinian organization probably in the world and we do great work.

Stacy: And you yourself are Jewish, if I may ask?

Sarah: Sarah Schulman.

Stacy: I don’t want to take any leaps here. [laughs] But that’s kind of interesting.

Sarah: I have two Jewish names, Sarah and Schulman.

Stacy: And you still teach at that school?

Sarah: Yes, I’m a distinguished professor at City University.

Stacy: I know that you have a pretty complicated relationship, or at least a very considered and thoughtful relationship to your professorship, as someone who thinks a lot about gentrification and access. You talk about that a lot in Gentrification of the Mind, sort of like your conflicting feelings about your role. I’m also an adjunct professor and I’m curious --

Sarah: Yeah, I’m living off your labor, basically.

Stacy: I guess I’m curious to know your politics about -- I should mention you also teach outside of formal education. You have a…

Sarah: Yeah, I run groups in my apartment. This year I’m running a group for people to turn their dissertations into books. I’ve run that for three years now. So yeah, I run non-academic programs. I also teach improv and sound, and I teach for Lambda Emerging Gay Writers, a queer writers program. I teach a lot in the community.

Stacy: Do you feel like you’re -- is the reason why you continue to teach at -- obviously we all need to survive and make a livelihood…

Sarah: Do you mean, if I was offered a job at NYU, would I take it?

Stacy: Yeah, or…

Sarah: Yes, at this point I would. If it paid enough.

Stacy: And is the difference there that it’s a private college?

Sarah: Well, you can’t negotiate your salary at CUNY because you’re a city employee. So it’s on the same system as firefighters and cops and sanitation workers. You know that because you’re a city employee.

Stacy: You seem very conflicted about it in Gentrification of the Mind and I’m curious about if it ever gets to be -- I also feel like, just from what I’ve read and my perception of you, you seem to live a very ethical life. At least, you try to live an ethical life.

Sarah: I’m glad you think that. Many people don’t feel that way about me. [laughs] I do try.

Stacy: It seems like that’s against some of your ethics -- your role at the school.

Sarah: Well, that’s discussed in Gentrification of the Mind. Like, you have to live and survive, right? And self-destruction doesn’t help anybody. You know, I’m a good teacher. I’ve helped a lot of people. I’ve mentored two generations, at this point, of queer and left-wing writers. I’m proud of that.

Stacy: Can you talk a little bit about how you ended up as a distinguished professor, considering the fact that you do not have -- Conflict is not Abuse and Gentrification of the Mind -- you make a point in the beginning of both texts to say that these are not academic texts.

Sarah: Right, I don’t have a master’s or anything like that. I barely have a B.A. My B.A. is from Empire State College. So the reason I became a distinguished professor is I was hired at the College of Staten Island in 1999 to teach fiction writing at a time when they had something called professional equivalence, which meant if you didn’t have a Ph.D, at the time I had published nine books and they accepted that as the equivalent of a Ph.D. This doesn’t exist anymore.

Stacy: That’s a shame.

Schulman: So if I applied today, and I’m about to have my 20th book come out, I would not be able to get hired. You have to have a terminal degree. So I got hired under that system. Now at that school, at that time, there were very few people who published a lot, and I published a lot, and so every time I published, I got promoted. The distinguished professor is a CUNY-wide position and my school didn’t have one in the humanities. It was beneficial to the school for them to have one. So they looked around and I was the most published person, I had a Guggenheim and all this stuff, and they were like, Let’s go with her. It took five years, the application process was five years. I had to get 30 letters of recommendation.

Stacy: [laughs] I don’t even know 30 people.

Sarah: Finally I got it.

Stacy: As a professor, something that I think a lot about is this concept of trigger warnings and what’s appropriate to discuss in class and what’s not appropriate. How to navigate that space, which is, again, another place that’s supposed to be safe and inclusive. I just wanted to read this paragraph and maybe you can elaborate on it a little bit:

My view, in sum, was that while sexual and physical abuse does occur on campuses and prejudice and discrimination may be rampant in class, actual sexual and physical abuse does not usually take place in a classroom. So intellectual, educational settings are among the few places in life where these things can be analyzed and engaged with in-depth without threat of actual, physical danger. Being reminded that one was once in danger has to be differentiated from whether or not one is currently in danger. Confusing the two is a situation which quickly becomes destructive. Being conscious about one’s own past traumatizing experiences and how they manifest into current traumatized behavior can be a force for awareness of one’s own reactions, not a means of justification for the repression of information. Additionally, as a teacher I oppose all restraints from administrations on classrooms.

I find that to be a very helpful guide. It makes total sense to me that some self-reflection is involved in one’s participation in a classroom setting.

Sarah: I teach at the College of Staten Island and of the 23 CUNY campuses, ours is the second from the bottom. That’s measured by graduation rate, so our graduation rate is 29%. It’s a very poor school. Also, many of the students are immigrants. No one at my school has ever asked for a trigger warning. The only student who ever did was someone who wanted to be told if the teacher was going to say that the Bible was not the Word of God. My students have the opposite problem. They live with a lot of violence. We have a lot of police officer families at our school, and correction officers at Rikers and stuff like that. Our students live with a lot of violence and they’re not sure that that is a problem. And because I teach fiction writing, they write about it all the time and they’re always grappling with the question of, is their father’s violence wrong? It’s a completely other discussion. It’s just not an issue there.

Stacy: Do you find that in these other classes that are outside of academic settings, like in your apartment, do you find that that becomes more of an issue?

Sarah: Never. Nobody would come to my apartment if they wanted a trigger warning. [laughs] But when I teach creative writing -- this semester I’m teaching night school on Friday night, which is very interesting. My rule in the class is that there’s no censorship whatsoever. Students can say any words they want, they can write about anything they want, they can do anything they want. But if other people don’t like it or are offended, they have to hear that and they have to listen to what other people say. I treat them like artists. You know, I’m an artist and how could I possibly impose censorship on other students? It doesn’t make any sense.

Stacy: I feel like in artistic communities, though, that seems to be where -- it’s some of the more progressive people I know who support the use of trigger warnings. Maybe this has to do with a sense of duty to protect others or something like that.

Sarah: Well, let’s get to the core of the word. I do define in the book what a trigger is. To me, it’s when unresolved pain from the past is experienced in the present. The question is, do you make the present accountable for pain that the present has not created, or do we help each other try to resolve and identify that this pain is from the past? I prefer the second because you can control every single word in the classroom, but what’s going to happen on the way to the classroom? There’s no way to monitor actual life. I think it’s beneficial to grapple with ideas that are disturbing.

Stacy: Is that information that you share with your students on the first day of class?

Sarah: I tell them there’s no censorship, yeah.

Stacy: I really appreciate how confident in these ideas you are, because I feel like there’s a lot of debate or hemming and hawing, and there’s something about all your writing that is so self-assured and well-researched.

Sarah: It’s multiple drafts, is what you’re reading. That book is very processed. You know, I really worked hard on it. I wrote it and rewrote it and I had other people read it and discuss everything. You know, I wanted to be accountable.

Stacy: Did you have to deal with a lot of pushback from people within your own community, like artistically and politically, about the things you were writing?

Sarah: Not pushback, but discussion. I mean, two of my young friends, Will Burton and Lana Povitz, who were both under 30 at the time, read the entire thing and gave me written notes on everything. There was cross-generation discussion. But, no, it’s not pushback, it’s what we all want. It’s engagement.

Stacy: Yeah, that’s an important distinction. Makes me think I should be more careful with my words. Maybe we could talk a little bit now about Gentrification of the Mind, which I read after Conflict is not Abuse. It’s the most engaged I’ve been with a book in a long time. In Gentrification of the Mind you talk about your own experience during the AIDS crisis but also drawing parallels between the gentrification that was occurring in the Lower East Side and how the AIDS crisis was used as a mechanism to facilitate a larger influx of --

Sarah: I’d say it’s a coincidence, not a conspiracy.

Stacy: As I was reading this, it made me wonder how…you talk about “responsible,” being a “responsible transplant” into a community. Because people move, right? That’s inevitable. Most people don’t stay in the same place forever. But you talk about how your generation, perhaps, was more responsible in its integration into community than later waves of --

Sarah: Well, I was born in New York. But I think people that came from small towns or other countries came to be part of New York. I think that after World War II, the phenomena of the suburbs, which was something that never existed before, produced a different kind of citizen. Because it was so privatized and so monoracial and had compulsory heterosexuality and was so consumer-oriented, those people were the gentrifiers. They came to change New York, instead of to become New Yorkers.

Stacy: Were you raised in New York City, or were you raised…?

Sarah: Yes, I’m from New York, New York.

Stacy: That made me wonder, I live in Windsor Terrace, which is a pretty white, middle class neighborhood of Brooklyn. I was raised on Long Island and have been in Brooklyn for probably 12 years now. It made me wonder, is gentrification individual people going and doing --

Sarah: No, no, not at all. That’s one of my larger arguments. Gentrification is policy. And I show, starting with white flight and the GI Bill, how gentrification became a way for the government to put money in the hands of developers. When gentrification first started, the argument was that it was natural evolution, but that’s completely false because they stopped building low-income housing, they gave tax cuts to developers like Trump -- corporate welfare, basically -- and it was determined. And it can be undone. If we had 500,000 affordable housing units in New York, there would be no more gentrification. And there’s things that we can do right now, like a vacancy tax, commercial rent control, fining people when they buy to flip, rather than to live. There’s lots of ways that we could change this but there’s no political will for it because, you know, people like De Blasio, who I unfortunately voted for - he’s such a disappointment to me - he promised 200,000 affordable housing units and then he didn’t deliver. But that would have made a difference in the city.

Stacy: You know, we’re in Chinatown right now. Montez Press Radio is in a multipurpose building. I’ve tried to do some research about the history of this building. I was curious about what used to be in this space. We have residential apartments above us, a skateshop below us. I’m wondering, do you have suggestions for us, as an organization, how to responsibly engage with this community so that we can do our small part and maybe not perpetuate the disintegration of Chinatown?

Sarah: Funny that you’re saying this, because I think eight years ago I was invited to a white gallery that was opening in Chinatown and they were like, “What should we do?” and I was like, “Show some Chinese artists. Go upstairs and ask the people who they think is a good artist.” Now, I don’t even know if there’s still Chinese people in this building or not.

Stacy: There are, thankfully.

Sarah: So ask them. The best way to work with people is to ask them what they need. That’s usually the first step, right?

Stacy: I’m happy to say that I think we have done a little bit of that here, but we could do more. And would you say that we should not be buying from places like Dimes and places like --

Sarah: I can’t say. I don’t know.

Stacy: Because you don’t know what that is?

Sarah: I don’t know the neighborhood. I know my neighborhood, but here?

Stacy: But probably an important part of it also is to educate oneself. If we’re gonna be here for a while, hopefully…

Sarah: The best thing is to get involved in your block association. Is there a tenants’ association on this block, or in this building?

Stacy: I’m not sure.

Sarah: Go to the Chinatown tenants’ places and ask them advice. Communicate.

Stacy: Part of that to me seems intrusive or something, but I guess --

Sarah: Well, if they think that you shouldn’t do it, then they’ll tell you.

Stacy: It all seems so obvious... [laughs] You talk, in the beginning of Gentrification of the Mind, also about representation in popular culture, which I think goes back to what you’re saying now about just asking and including people. But I was curious -- you say something toward the beginning of the book about -- you ask if there will ever be a lesbian lead in a movie, and you talk a lot about representation in literature and stuff. This was published in 2012, so I’m not sure if since that time we have gotten a lesbian, female lead?

Sarah: Well, it’s 2019 and there still has not been a bestselling novel with an authentic lesbian protagonist since Rubyfruit Jungle in the 70s.

Stacy: Because I feel like there’s also a danger of whitewashing, what’s the difference between positive representation and just representation? So that you don’t gentrify, perhaps, the idea of what lesbian writing is.

Sarah: Positive representation is when a person is presented as a fully complex human being in a fully nuanced, complex context. That’s what I strive for all my life. That’s what I’ve been trying to do, and that is something that has not been commodified yet.

Stacy: But I guess my question is, when it’s commodified, does the commodification of that representation ultimately lead down the path of…

Sarah: Well, what are you thinking of? Do you have something in mind?

Stacy: Something like Boys Don’t Cry. Obviously there’s problems with that because the actors were not trans people --

Sarah: I totally disagree with that criticism.

Stacy: What, that they weren’t trans?

Sarah: First of all, given the time in which it was made and the obstacles that Kimberly faced -

Stacy: I mean, I love that film, that’s not --

Sarah: I don’t think that’s a legitimate criticism. Also, that character was not a trans person. They had not gone through transition.

Stacy: They had actually, also, in real life -- I think that they, themself, hadn’t -- but I guess that’s what I mean. When the film was made and everyone started calling that main character trans, which simplified --

Sarah: Well, it took awhile for that to evolve. I mean, Donna Minkowitz was a reporter for the Voice who famously argued that it was a lesbian character. There’s an interesting professor at SF State, Nan Alamilla Boyd, who has this great article on telling lesbian history and trans history to the same bodies, that it’s not an either-or, and it’s very helpful. I use it in my book that I have coming out next year.

Stacy: I wondered if the telling of that story -- that’s something that I’ve talked about in my class, and that’s an interesting film to show because there’s the question about trigger warnings.

Sarah: You know, in the documentary about Brandon Teena, right, where they interview the actual, real people, they interviewed his real girlfriend, whose name I forget right now, who was played by Chloe Sevigny in the movie. And she said, “Brandon was -- she was the best boyfriend I ever had.” And there you have it.

Stacy: Something that I also noticed is, some of the nuances that you use in these books, like Abuse is capitalized in Conflict is not Abuse, and in Gentrification of the Mind you say how in the New York Times, they didn’t print the word gay, but I’m assuming they were using homosexual?

Sarah: Oh no, yeah, they would use homosexual. But gay was not acceptable.

Stacy: I guess I had a question about that, because they even, when they refer to Trump, or any standing President, as Mr. Trump or some of of these colloquialisms -- although with gay, they were using more scientific language I guess?

Sarah: Well, the New York Times was incredibly homophobic. If a person died of AIDS, they wouldn’t say so. They wouldn’t allow you to be “survived by your partner.” They would not allow you to be gay. And they notoriously did not cover the AIDS crisis until they were forced to by activists. The New York Times was the enemy of gay people for quite some time.

Stacy: Do you feel like that still…?

Sarah: Well, I think their coverage is quite questionable now. They have coverage now, which they didn’t have before, but it’s not that helpful.

Stacy: But I guess I was curious about this distinction between a word like homosexual and a word like gay, and what is meaningful to you about these different --

Sarah: Well now, the difference is irrelevant, I think. But at the time, homosexual was the technical word and the legal word, right? Gay was the self-chosen word.

Stacy: So maybe more humanizing? [pause] I watched the film that you co- produced, United in Anger, and that’s a wonderful, amazing film. It made me feel so, like, in the same breath, totally empowered and totally, not disempowered, but just like, what do I do? Because obviously we live in a time where there’s a lot that needs to be done. It seems like ACT UP was so…you were very involved in ACT UP. Something I was intrigued by was your decision to include a clip of yourself in that film, of you --

Sarah: Being wrong. I shot myself being wrong.

Stacy: [laughs] Why did you choose --

Sarah: We just felt like, you know, why shouldn’t we show ourselves being wrong? Why create this heroic facade?

Stacy: But I think that your idea, basically, in the film, there’s a clip of you, after the protests in the church. Maybe you can --

Sarah: Cardinal O’Connor was trying to keep condoms out of the public schools and we felt that people would die from that policy. So ACT UP decided to, in a sense, disrupt Mass as a protest. But the plan was to do a silent die-in, and in our film we show footage of ACT UP planning a silent die-in. So people got in the church, I was in the church, but then, unexpectedly, Michael Petrelis, one of the activists, jumped up on the pews, blew a whistle and screamed, “You’re killing us!” And that just started total chaos. People were screaming, a lot of people got arrested, it was a complete zoo. And when I came out of there, somebody put a mic in front of my face and I thought that it was wrong, I knew that because I saw that it alienated parishioners. But I was wrong because it actually made an incredibly important statement - that people with AIDS were not going to just lie down in front of some concept of privilege, bowing to the Catholic church. It resonated all over the world. People with AIDS and gay people all over the world saw the message of resistance. It was one of our best actions.

Stacy: I respect that type of self-reflection in the film, but I’m wondering if you have recommendations or suggestions for how… I feel like when protests are organized now, and everyone’s in Union Square and everyone’s yelling, it feels like there’s no ask. There’s this element of vanity to it that doesn’t seem totally productive. I’m wondering why you think that is, because obviously we still, I mean, the crisis of AIDS, the intensity of and the rate of death was very high, obviously, but…black people are dying, immigrants are dying, there is violence and tragedy that is quantifiable. I’m just curious why not now?

Sarah: Well, my next book is an 800-page history of active New York and it’s based on 188 interviews I’ve done over 18 years. I totally cohere exactly what the strategies were. In fact, the introduction is a 70-page pullout with exactly the things that you’re asking for: how to build a campaign instead of a one-shot deal, how to mobilize the people that show up to you events for something coming after, how to do affinity groups. You know, it’s all the how-to’s to get an effective movement. But the biggest message of my book, I’m going to just give it away now and it’s not coming out until February 2021, is that ACT UP was effective because they did not have consensus. For a lot of other reasons too. But they didn’t try to force people to agree, and they didn’t try to cohere one strategy. So if you wanted to go to the Lower East Side and illegally hand out needles in order to be arrested to do a test case trial so that needle exchange would be legal in New York, and I didn’t want to, I just wouldn’t go, I wouldn’t try to stop you from doing it. [laughs] So there was all this simultaneity. Everyone did what they thought was a good idea at the same time and it created this paradigm shift. Today we’re in the opposite mode and it doesn’t work. Trying to force people to agree on an analysis, or which words to use, even, has never worked. There’s no example in history of it ever working, and it doesn’t work now. So simultaneous, proactive direct action is a better way to go.

Stacy: It seems like the first meetings of ACT UP were more localized in terms of -- you know, it must have started with just a few people, right?

Sarah: It started with a few hundred people.

Stacy: So how did that, I mean, if Tom and I wanted to start some sort of direct action group --

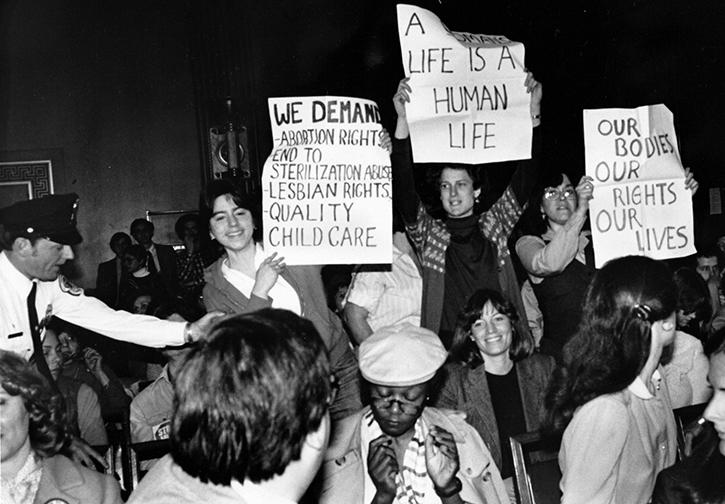

Sarah: Oh, five people can be very effective. You don’t need a few hundred people. But what you do need is an action that will have an impact and that has a future. Like for example, in one of the vouchers of the Lesbian Avengers -- and that’s a very interesting story too, in my book My American History I have all the documents that discuss quite a bit of the strategies that they used -- we had a whole bunch of rules because we had a constituency that had been raised to not have any power. You know, this was 1992. Lesbians were very marginal and were profoundly oppressed at that time, and still are. So we were like, “If you disagree with an idea, you have to make a suggestion for an alternative. If you have an idea, you have to do it.” You know, it was all this structure so that you couldn’t just pontificate or obstruct or anything like that, you had to develop a vision and carry it through. The more you empower your membership to do things like that, the more effective you will be. You know, I was in a five-person group called the Women’s Liberation Zap Action Brigade. In 1982 we interrupted an anti-abortion hearing in Congress on live television. So when you do that, I mean, there’s no live television anymore, but you know, you’re looking at what is going on in your time and how can you get the biggest impact. That had an enormous impact. Or like, when we organized the first Dyke March, the Lesbian Avengers organized that, there was a gay march on Washington and it was co-opted by the Democratic party. So we went with these club cards, we said come to this event, we had no permit, we had no corporate sponsorship, we had nothing, and 20,000 women showed up. But they had come from all over the world to Washington for this gay march. Well, then they went back to where they came from, and the next year they all did Dyke Marches, so it spread. You know, five people can do a lot.

Stacy: Do you feel like when one does something like interrupt live television -- obviously, when you’re doing something like interrupting pro-life --

Sarah: We don’t use that term, you know. Anti-abortion.

Stacy: The ask, or the demand there, was to keep abortion --

Sarah: The bill was called the Human Life Statute, and what we said was, “A woman’s life is a human life.” It was very young women rebelling and saying, “No, we don’t agree, we don’t agree to stand by and watch this happen.” You see it in the Palestine solidarity movement all the time - people are constantly disrupting right-wing Zionist events and such. But your message has to be clear. Do you know Rise and Resist?

Stacy: I don’t.

Sarah: So some old ACT UP people started a group called Rise and Resist. They do anti-Trump demos every week. They have a Facebook page.

Stacy: I’ll check that out. Yeah, there’s a few…I’m a PEN Prison Writing mentor and I’m trying to get more involved in PEN and in anti-incarceration legislation, but I feel like, do you feel like just going to a protest where there’s maybe… What was the protest the other day in Union Square, Tom? I think there was an environmental event happening. Do you think it’s effective to just have a bunch of people… it’s better than nothing, but I’m wondering if you feel like that’s an effective mode of --

Sarah: No, it’s been outmoded for decades. Direct action is much more effective. You know, the most famous action in American history was when Black students sat in at segregated lunch counters, right? That image of them sitting there, and the racists throwing food at them, and them just sitting there -- what they were doing is, they were creating an image of the world that they wanted to have. They weren’t marching around outside, with signs saying Integrate This Lunch Counter. They integrated the lunch counter. So that’s what direct action does. You put your body on the line and create the image of the world you want. It’s creative and it’s participatory. Marching around and listening to speakers is totally outmoded and I don’t think it’s effective.

Stacy: Yeah, I think that the participatory aspect seems very crucial and I kind of want to end on that note because it feels very poignant to me, and after this interview I’m going to look up -- was it Rise and Resist? -- and hopefully become more involved in the community of Chinatown. Thank you so much for joining us and helping us learn.